MCNY Blog: New York Stories

Iconic photos of a changing city, and commentary on our Collections & Exhibitions from the crew at MCNY.org

Bittersweet: The American Revolution and New York City’s Sugar Industry

Levi Hanford sat confined in a crowded cell. He dropped a moldy biscuit and a small ration of pork into a kettle filled with water. As the bread slowly broke apart, he skimmed the worms from the kettle and then boiled the ingredients together. British soldiers captured Levi in 1777 while he served as a revolutionary guard on Long Island at the age of seventeen. Along with his fellow detainees, Levi suffered from the poor diet and the tight quarters, both of which spawned the rampant spread of disease. Scurvy infected the inmates, causing their teeth to fall out and their gums to bleed. His detainment was not only harrowing but unusual, for his captors imprisoned him in an old sugar refinery. Levi’s experience provides an intimate glimpse into the types of personal hardships faced during the Revolution. It also demonstrates how the sugar industry, which eventually became central to New York City’s commerce and created incredible fortunes for families like the Havemeyers, became entangled in the fight for independence.

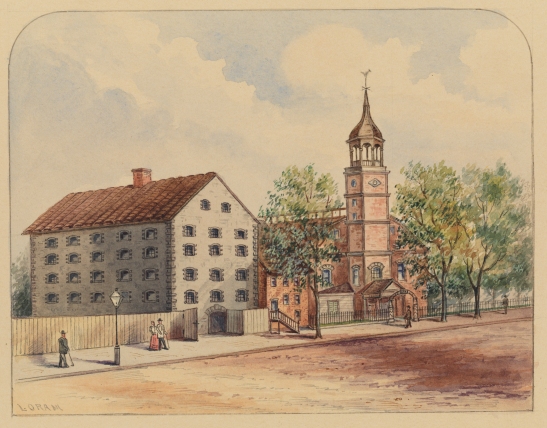

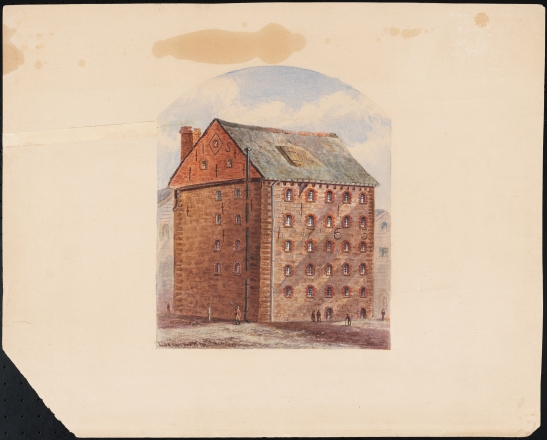

Nicholas Bayard opened the first sugar refinery in New York City in 1730. The local demand for sugar and the city’s accessible ports fueled the importation of raw sugar into the colonies from overseas. Soon many eager businessmen began to build refineries in lower Manhattan. The buildings, made of large granite blocks, presided over the neighborhood as looming symbols of a burgeoning industry.

While the sugar business continued to grow, tension spread throughout the colonies, eventually erupting into the American Revolution. Beginning in 1776, New York City served as the headquarters for British operations in North America. As they captured insurgents – soldiers, sailors, and civilians alike – they detained them in both private and public buildings, including churches, dismantled warships, classrooms at King’s College (now Columbia University), and sugar houses. Prisoners suffered from deplorable conditions. Some survivors described fellow inmates who ate their own shoes and clothes out of pure hunger. Overall, approximately 30,000 Americans were confined in New York during the Revolutionary War. An estimated 60 to 70 percent of those imprisoned died.

The British used two sugar houses as prisons. The first was Livingston’s, on Crown (now Liberty) Street, and the second was Van Cortlandt’s, which stood on the northwest corner of Trinity Church yard. In the late 19th century, stories circulated that claimed a third sugar house, called Cuyler’s, also served as a Revolutionary War prison. In fact, two windows from the old refinery, later referred to as Rhinelander’s, were preserved as monuments to those Americans who died in the Revolution. The first window sat embedded in the Rhinelander building until 1968. It now lives at One Police Plaza. The second window currently rests at Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. Despite the windows’ preservation, little evidence suggests that the Cuyler sugar house served as a prison. In fact, scholar Edwin G. Burrows maintains that Henry Cuyler was a Tory and, as such, his refinery continued to process sugar throughout the British occupation. In any case, the windows still stand as a marker of that era and the Museum of the City of New York has a key and lock set from the Rhinelander sugar house.

Lithograph issued by A. Weingärtner’s lithography. Rhinelander’s Sugar House & Residence between William & Rose Sts. 1857. Museum of the City of New York. 92.5.7

Unknown. Lock & key from old Rhinelander’s Sugar House, Rose & Duane sts., ca. 1769. Museum of the City of New York. 29.64A-B

Key [Key to the old sugar house prison of revolutionary days], late 18th century. Museum of the City of New York. 37.352

Robert L. Bracklow (1849-1919). Old Sugar Houses, Rose Street [View of the Rhinelander Sugar House at the corner of Rose Street and Duane Street after a fire], ca. 1890. Museum of the City of New York. 93.91.200

![[Rhinelander Building.]](https://blog.mcny.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/8-rhinelander-building-with-window_x2010-11-3212.jpg?w=547&h=389)

Window from the Cuyler / Rhinelander sugar house embedded in the Rhinelander Building. Unknown. [Rhinelander Building], March 1968. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.3212

![[Detail of window from Old Sugar House in Rhinelander Building.]](https://blog.mcny.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/detail-of-window-in-rhinelander-suagr-house_x2010-11-3213.jpg?w=547&h=774)

Unknown. [Detail of window from Old Sugar House in Rhinelander Building.], 1973. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.3213

Ruin of the “Old Sugar House” Prison. Now in Van Cortlandt Park, New York, ca. 1910, in the Postcard collection. Museum of the City of New York. F2011.33.1485

The use of the sugar houses as prisons during the American Revolution marks a darker period in the sugar industry’s history; yet, the business eventually returned to, and then surpassed, its former prominence. William Havemeyer (1770 – 1851) and Frederick C. Havemeyer (1774 – 1841) influenced the industry tremendously. Decades after the Revolution, they opened their own refinery. Its daily capacity of raw sugar – 300,000 pounds – exceeded that of all other New York City refineries combined. Their success continued. By 1870 their firm employed about 1,000 workers per shift and their factory stored over one million pounds of sugar a day. The Havemeyers’ prosperity is evidence of the sugar industry’s growth throughout New York City at that time. In fact, from 1870 until World War I, sugar refining became the city’s most profitable manufacturing industry, and the Havemeyer family continued to reap the rewards of such a lucrative business. By 1907, a loose network of companies controlled by the family accounted for approximately 98 percent of national production. The Havemeyers’ good fortune continued through subsequent generations and can be seen in the refined décor of Theodore Havemeyer’s house, located at Madison Avenue and 38th Street. Theodore (1839 – 1897) had followed his grandfather, Frederick C. Havemeyer, into the sugar business, thereby furthering the family’s legacy.

Byron Company. The Havemeyer House at the corner of Madison Ave. and 38th St., 1898. Museum of the City of New York. 93.1.1.17150

Byron Company. Interiors, Theodore Havemeyer House, Music Room, ca. 1893. Museum of the City of New York. 93.1.1.17529

Byron Company. Interiors, Theodore Havemeyer House, Chinese Room, ca. 1893. Museum of the City of New York. 93.1.1.17530

Byron Company. Interiors, Theodore Havemeyer House, Dining Room, ca. 1893. Museum of the City of New York. 93.1.1.17526

Sugar production developed into a flourishing industry that supported New York City’s commercial growth, provided jobs to thousands of workers, and created tremendous wealth for families like the Havemeyers. But amid all the positive aspects of the industry’s history, the sugar houses’ role in the American Revolution cannot be forgotten. The Livingston and Van Cortlandt sugar refineries contributed to the economic success of an industry and a city, yet they also became a site of detainment and suffering. The experience of imprisoned patriots, like Levi Hanford, who languished in the sugar house prisons, reminds us that history is not always sweet.

Works Cited

Bradley, James, and Rowan Moore Gerety. “Sugar.” The Encyclopedia of New York City. Ed. Kenneth T. Jackson. Second ed. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1995. 1263-264. Print.

Burrows, Edwin G. Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War. New York: Basic, 2008. Print.

Burrows, Edwin G. “Sugar Houses.” The Encyclopedia of New York City. Ed. Kenneth T. Jackson. Second ed. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1995. 1264. Print.

Burrows, Edwin G. “The Prisoners of New York.” Long Island History Journal 22.2 (2011): n. pag. Long Island History Journal. Stony Brook University. Web. 22 May 2015.

Hanford, WM. H. “Incidents of the Revolution. ;Recollections of the Old Sugar House Prison – Interesting Letter.” Editorial. The New York Times 16 Nov. 1852: n. pag. Incidents of the Revolution. The New York Times. Web. 22 May 2015.

“Havemeyer, Theodore A., 1839-1897.” Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America. The Frick Collection, n.d. Web. 22 May 2015.

Amazing. Certainly didnt know all that before. Thank you for organizing all these information with great photos!

Having just completed a comprehensive book on the Rhinelander family, I am pleased to find that your blog author does not continue the myth that the Cuyler/Rhinelander Sugar House history, usually referenced as a prison during the revolution, has been corrected.