MCNY Blog: New York Stories

Iconic photos of a changing city, and commentary on our Collections & Exhibitions from the crew at MCNY.org

Gustavademecum: a dining guide for engineers and explorers

As fluid as the New York restaurant scene has always been, one thing has stayed the same: We are a city of discerning diners. So what did New Yorkers do before restaurant apps, before dining guidebooks, and survey ratings? Did we rely merely on word of mouth to uncover the best appetizer on the Upper East Side, the most kid-friendly lunch spot with a water view?

The Museum’s Manuscripts and Ephemera collection recently accessioned an object that helped me discover that the trend of reviewing and quantifying dining experiences did not begin in the 21st century with Yelp. The Gustavademecum for the Island of Manhattan or, A Check-List of the Best-Recommended or Most Interesting Eating-Places, Arranged in Approximate Order of Increasing Latitude and Longitude is an independently published guide to dining in Manhattan by Robert Browning Sosman (1881-1967). Sosman was an accomplished physical chemist and professor who lived in New Jersey and frequented New York City for business. Between 1941 and 1962 Sosman compiled data about his many meals in Manhattan restaurants and hotels, and self-published a yearly guide to distribute to friends and at conferences. The Museum’s edition dates from 1954.

Robert Browning Sosman. Gustavademecum for the Island of Manhattan, 1954. Museum of the City of New York. 2016.17.1

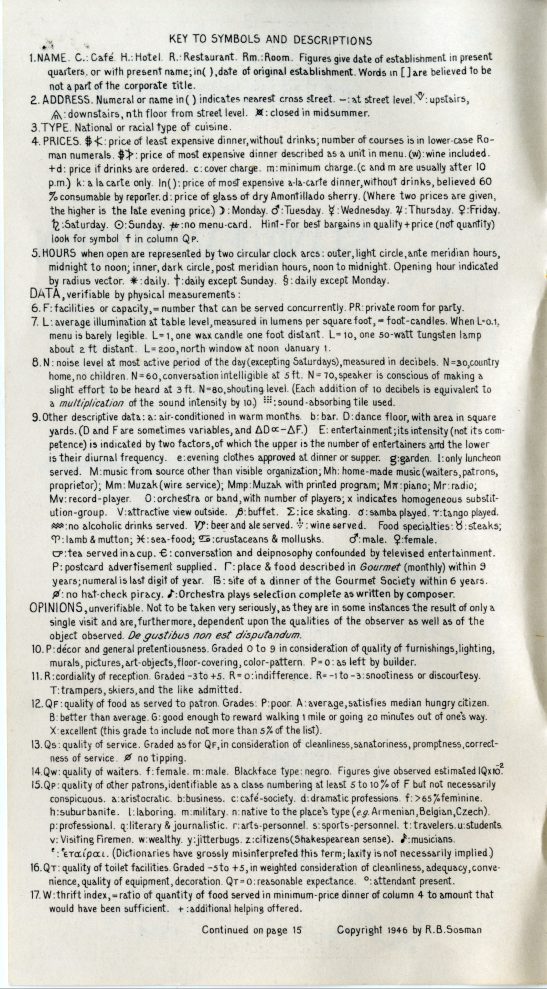

“Gustavademecum” loosely translates from Latin as “taste with me.” The guide is clearly aimed at a data-minded audience, and Saveur magazine describes it as a “gastronomic brain trust”. The pocket-sized pamphlet is organized geographically – the 300 selected restaurants are arranged in order of increasing latitude and longitude – beginning with the southern end of Manhattan. The entries include the usual, in-demand information about a restaurant, including its address, type of cuisine, price, and hours. The guide also includes more unusual information, which Sosman quantifies as either “data” or “opinions.” Data categories include the average illumination at a table, measured in lumens, and the “noise level at the most active period of the day,” measured in decibels. A restaurant could rate at the quiet end of the scale, “N=30, country home, no children”, to the very loud, “N=80, shouting level”. The “opinions” alert diners to the quality of décor, service, other patrons, and toilet facilities. Other patrons could fall into several categories, including business, suburbanite, students, jitterbugs, and “citizens (Shakespearean sense).” Diners could also refer to the Gustavademecum to check what type of music would be played in an establishment, whether or not “piracy” was apt to occur at the hat-check, or what level of “cordiality of reception” to expect. What makes the guide unique is that all of this descriptive information is communicated with a Sosman-designed system of glyphs, Greek letters, and mathematical and astrological symbols.

Robert Browning Sosman. Gustavademecum for the Island of Manhattan, 1954. Museum of the City of New York. 2016.17.1

Robert Browning Sosman. Gustavademecum for the Island of Manhattan, 1954. Museum of the City of New York. 2016.17.1

The Gustavademecum offers a more personalized account of what it was like to dine out in Manhattan during the 1950s, and complements the Museum’s collection of hundreds of restaurant menus; several establishments included in the guide are represented in our collection. According to the guide, diners visiting Adolph’s Asti Restaurant on East 12th Street could enjoy Italian fare that received a G- rating, just below “good enough to reward walking 1 mile or going 20 minutes out of one’s way”. Entertainment in the form of piano and “home-made” music was provided every day by four entertainers, and other patrons typically included suburbanite types, arts-personnel, and travelers. However, diners would almost need to shout to hear each other, and the toilets received a rating of 1.6 out of 5. Sosman noted the restaurant’s 580 opera and stage portraits as memorable, but he gave the overall décor a rating of just a 1 out of 9.

Just as diners today must take Yelp reviews with a grain of salt, Sosman prefaces his opinions with a disclaimer, “Nota bene! De gustibus non est disputandum.” Translation: “There is no disputing about tastes.”

The Museum is grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities, whose support has allowed us to digitize and share the menu included in this post, along with several thousand other images from our ephemera collections. The remainder will be available by early 2017.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Related

Information

This entry was posted on October 4, 2016 by Emily Chapin in Manuscripts and Ephemera and tagged 20th century, Customer reviews, Customer satisfaction, Data, Dining, Ephemera, Ratings, Restaurants, Robert Browning Sosman (1881-1967).Shortlink

https://wp.me/p1kGOJ-4PcArchive

- May 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (2)

- December 2017 (1)

- November 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (1)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (2)

- May 2017 (4)

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (4)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (4)

- November 2016 (5)

- October 2016 (4)

- September 2016 (4)

- August 2016 (5)

- July 2016 (4)

- June 2016 (4)

- May 2016 (4)

- April 2016 (4)

- March 2016 (6)

- February 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (4)

- December 2015 (5)

- November 2015 (4)

- October 2015 (4)

- September 2015 (4)

- August 2015 (5)

- July 2015 (4)

- June 2015 (5)

- May 2015 (3)

- April 2015 (6)

- March 2015 (5)

- February 2015 (4)

- January 2015 (4)

- December 2014 (4)

- November 2014 (4)

- October 2014 (5)

- September 2014 (5)

- August 2014 (4)

- July 2014 (5)

- June 2014 (4)

- May 2014 (4)

- April 2014 (4)

- March 2014 (4)

- February 2014 (4)

- January 2014 (4)

- December 2013 (4)

- November 2013 (4)

- October 2013 (5)

- September 2013 (4)

- August 2013 (4)

- July 2013 (5)

- June 2013 (4)

- May 2013 (3)

- April 2013 (5)

- March 2013 (4)

- February 2013 (3)

- January 2013 (5)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (2)

- October 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (4)

- August 2012 (4)

- July 2012 (5)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (5)

- April 2012 (4)

- March 2012 (4)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (5)

- December 2011 (3)

- November 2011 (5)

- October 2011 (4)

- September 2011 (3)

- August 2011 (5)

- July 2011 (4)

- June 2011 (2)